‘Get on it AY-sep!’ Foreign words have invaded Korea. The government is fighting back

SEOUL — Kim Hyeong-bae, a South Korean linguist, had a problem: how to translate the word “deepfake” into Korean.

A senior researcher at the National Institute of Korean Language, a government regulator, Kim works in the public language department. His job is to sift through the many foreign words that clutter everyday speech and bring them to the committee — called the “new language group” — to be translated into Korean.

”Deepfake,” which is pronounced dihp-PAY-kuh and has been appearing in newspaper headlines with increasing frequency, was a textbook candidate.

1

2

3

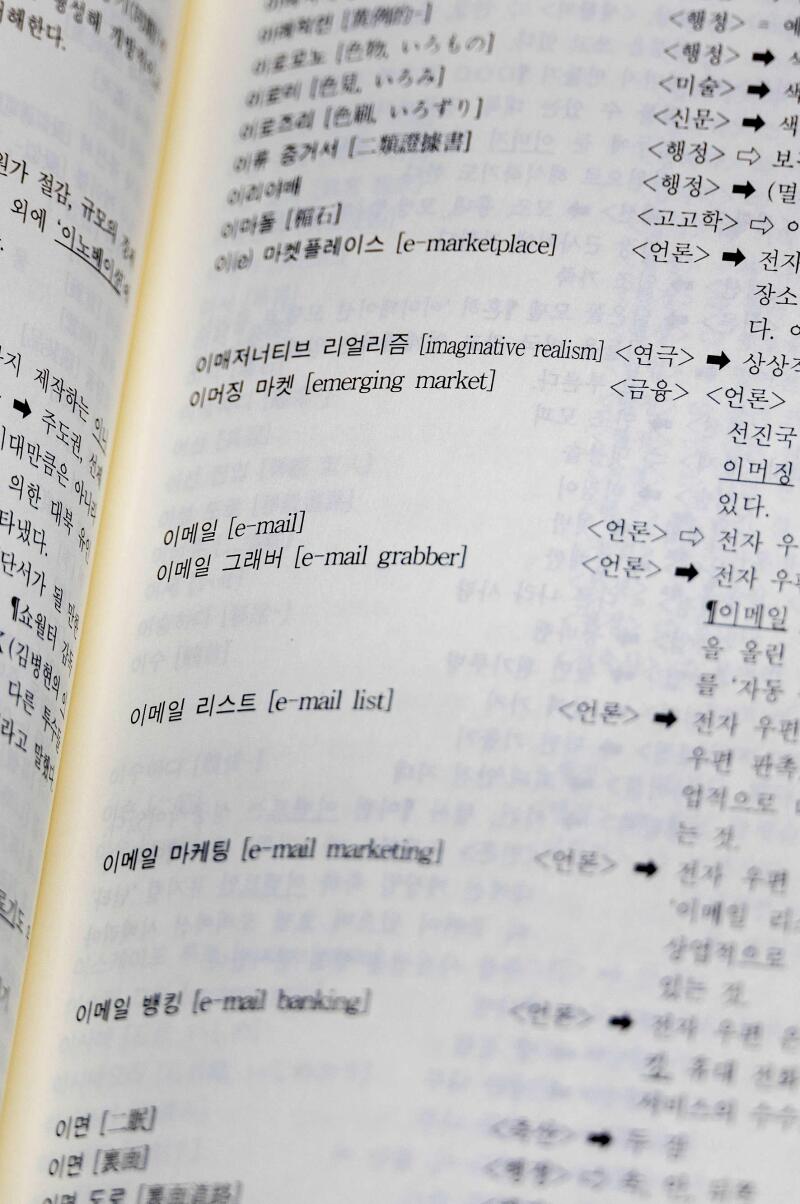

1. Korean suggestions of English words such as “e-mail” and “e-mail list” in the library at the National Institute of Korean Language in Seoul. 2. Kim Hyeong-bae, a senior researcher, inspects a relief sculpture of the book of the Korean alphabet in its original form displayed inside the institute. 3. Kim works in the public language department sifting through the many foreign words to find Korean equivalents.

A word-for-word translation would sound like nonsense, so Kim and 14 other language experts in a video conference last fall began with the essential questions: How could the word’s negative connotations be accurately expressed in Korean? And was it necessary to use qualifiers like “counterfeit” or “artificial intelligence”?

One participant suggested “intelligent modification,” only for another to object: “That makes it sound like a good thing.”

By the end of the 15-minute discussion, the options had been narrowed to five.

Later that month, the institute held a poll asking 2,500 respondents from the public to rate the suitability of each candidate, after which an external committee ratified a winner: “artificial intelligence-manipulated video.”

Then, by way of an entry into the institute’s public glossary of reworked foreign words, it was released back into the world.

Since the institute was founded in 1991, more than 17,000 so-called loanwords — nearly all from Chinese, Japanese or English — have been localized in this way.

Other countries have also tried to thwart the encroachment of loanwords. The French Academy, founded in the 17th century to guard “pure” French, has been railing against Anglicisms for decades. So has the Spanish Royal Academy. Even the British have been trying to swat back Americanisms.

All, for the most part, have been losing fights.

Likewise for Kim, the mission of tackling five new ones every two weeks can feel, to use a Korean idiom, like pouring water into a bottomless pot.

Kim Hyeong-bae, a senior researcher, searches for a book that describes loanwords inside the library at the National Institute of Korean Language in Seoul.

“We can’t rework loanwords as soon as they appear — we have to observe for a bit until it’s clear that it’s being used widely, after which we can step in,” Kim said. “But by then it’s already spread everywhere.”

It also doesn’t help that there are already so many of them, reflecting Korea’s long history of foreign influence.

Until the invention of the Korean alphabet in 1443, the elites of Korea’s dynastic kingdoms used hanja, the Chinese script that today still makes up the roots for many Korean words much like Latin does for English.

Japan’s colonization of Korea from 1910 to 1945 introduced loanwords including gao, Japanese for “face,” adapted into Korean as “put on gao,” which means to put on airs.

Some words have been lent twice, including why-SHAT-suh, which means dress shirt and is taken from a Japanese transliteration of “white shirt.”

Today, English is king. It is widely seen here as the language of cultural sophistication and a Western education, adopted by corporations, government officials and journalists looking to lend their speech more authority.

“The foreign languages that entered the country were always a tool and badge of the ruling class,” Kim said. “I think loanwords can be understood in those terms — as a way to signal your social position, to set yourself apart.”

The sheer clip at which English words rotate in and out of the vernacular has made it difficult for any statistic to accurately capture the scale of loanword creep. But it’s clear that the phenomenon is not just the tweedy concern of linguists.

Among the recent loanwords (or locally coined spinoffs) that have reached the institute’s chopping block: skimpflation, bundleflation, finfluencer (finance influencer), upskilling, upselling, cross-selling and value-up.

A giant Korean dictionary is on display inside the library at the National Institute of Korean Language in Seoul.

In a survey of 7,800 South Koreans last year by polling company Hankook Research, more than three-quarters said they frequently encounter foreign words in public speech, up from 37% in 2022. A majority said they preferred easy-to-understand Korean alternatives.

Even to native English speakers, the transliteration of familiar words into an alphabet with imperfectly matched consonants — lacking, for example, a precise “F” or “R” sound — can be confusing.

And in recent years, the oftentimes absurd incursion of loanwoards has become satirized in popular culture, with speech that needlessly shoehorns English in at every turn pejoratively referred to as “voguespeak” or “Pangyo dialect.”

The former is a reference to Vogue magazine, whose Korean edition is seen as particularly guilty of this, the latter to a city known as South Korea’s Silicon Valley, where you might hear a tech worker say a sentence like this:

“The pi-pi-tee (PPT, slide presentation) was a little LUH-puh (rough), but the NEE-juh (needs, demands of consumers) were clear and I think it’s worth eeshoo-RYE-jing (to raise an issue) AY-sep (ASAP).”

Fixing up loanwords is a dream job for someone like Kim, 59, whose obsession with the Korean language has given him what he describes as an occupational disease: wincing every time he walks down the street and notices all the signage with misspelled words, loanwords and malapropisms.

As a child, Kim enjoyed looking up words in the dictionary and learning their etymology, a hobby that endured into adulthood.

For Kim Hyeong-bae, the mission of tackling five new loanwords every two weeks can feel, to use a Korean idiom, like pouring water into a bottomless pot.

(Jean Chung / For The Times)

For the last 20 years, he has led an online community with about 10,000 members, where he publishes a regular column exploring the origins of words that caught his interest. The latest entry, No. 1,038, examines Korean substitutes for ”poncho.”

After attaining his Korean linguistics PhD, he taught at a university before realizing he preferred being out in the field, joining the institute in 2007.

“I wanted to make a difference and bring about change on a policy level,” he said.

One point of irritation he has developed over the years is the use of loanwords when the exact Korean word already exists.

In some cases — like SIGH-duh (side), the kind on a restaurant menu — the Korean word (gyeotdeuri) has become so neglected it has disappeared from mainstream memory.

Others, like “wife,” reveal more interesting tensions.

A survey the institute conducted in 2022 found that the majority of Korean men in their 20s and 30s described their spouses as WHY-puh (wife), probably because that feels more egalitarian and modern than ahnae, whose roots translate into “domestic person.”

Pedestrians in Seoul walk past stores whose names are in English.

(Jean Chung / For The Times)

Although he understands the rationale, Kim sees this as part of a wider trend of abandoning Korean words simply because they feel old-fashioned, fossilizing them even further.

And just as words and their meaning can impose a certain reality, the opposite also can be true: A word’s connotations can evolve alongside the things it denotes. Etymologies are not diktat.

“The underlying treatment of someone doesn’t change just because you rename them,” he said.

“Employers do this all the time. Instead of trying to change working conditions or benefits, they will just change the language in job titles.”

Kim is aware that some see his work as a little fusty and nationalistic — “North Korea-esque,” some have called it.

Past attempts to expunge loanwords after Korea’s independence from Japan had an element of ritualistic purification. But the institute’s current approach is largely about keeping the civic square accessible and fair.

“Language is a human right,” Kim said.

“Our job is about coming up with easier alternatives to foreign words that might be difficult for some people, so that there isn’t a class of the population that ends up marginalized.”

Studies have shown that the elderly and those without college educations struggle with loanwords, potentially shutting them off from government services or programs that feature them.

That makes some battles more important than others. One priority is translating loanwords that are being used to communicate public policy or important news events, such as “microcredit” or “voucher” as well as pandemic terms such as “booster shots.”

At the same time, there is no point trying to force out a loanword that has already become firmly entrenched, such as inteonet (internet) or dijiteol (digital).

Slang words such as billeon (villain, a humorous term for a public troublemaker) sit somewhere in a gray area.

Although the institute has recently offered up the Korean word for villain, akdang, Kim acknowledged it may be a tough sell.

Such is language: Some of it sticks, some of it doesn’t, and nobody can really explain why.

Kim looks at the statue of King Sejong, who invented the Korean alphabet hangeul in 1443, inside the language institute.

“Some things you just have to accept,” he said.

“Deepfake” might be one of them. The word had been reworked once already, in 2019, to “high-tech manipulation technology.” It had then probably been doomed by its wordiness.

And in the weeks after the institute’s second attempt, “artificial intelligence-manipulated video,” was faring no better — “deepfake” still abounded.

But by then, Kim had already moved on to the next batch of words.